Birds have several reasons for migration, but the most significant is the need to survive and reproduce, making migration important for birds. While food and nesting space are key factors, birds also migrate to find optimal conditions for survival and breeding. Harsh weather conditions, particularly cold temperatures, can be detrimental to birds’ survival, which is why they migrate to avoid them.

Seasonal changes in vegetation, influenced by wind, precipitation, and temperature, impact food availability and nesting space. This makes bird migration a seasonal phenomenon, as birds follow the available resources to ensure their survival and reproductive success. Witnessing large flocks of migrating birds is a stunning natural spectacle and a testament to the wonders of the natural world.

A history of bird migration

Such a phenomenon has long-since inspired curiosity amongst scientists and researchers. Until the early 19th century, there were some wild ideas to explain why bird populations were suddenly absent for certain parts of the year. For example, Aristotle believed that some birds went into hibernation and 17th century English minister, Charles Morton, claimed that birds flew to the moon and back each winter. However, in 1822 real evidence came to light when a hunter in Germany shot down a white stork with an arrow impaled through its neck.

The arrow turned out to be from central Africa confirming that the stork had travelled thousands of miles. Following this, in 1906, scientists began to put rings onto the white storks to learn more about where they wintered in sub-Saharan Africa. Since then, incredible advances in technology and satellite tracking have enabled researchers to explore in great detail what happens during bird migration and answer some of the many questions.

Where do birds migrate to?

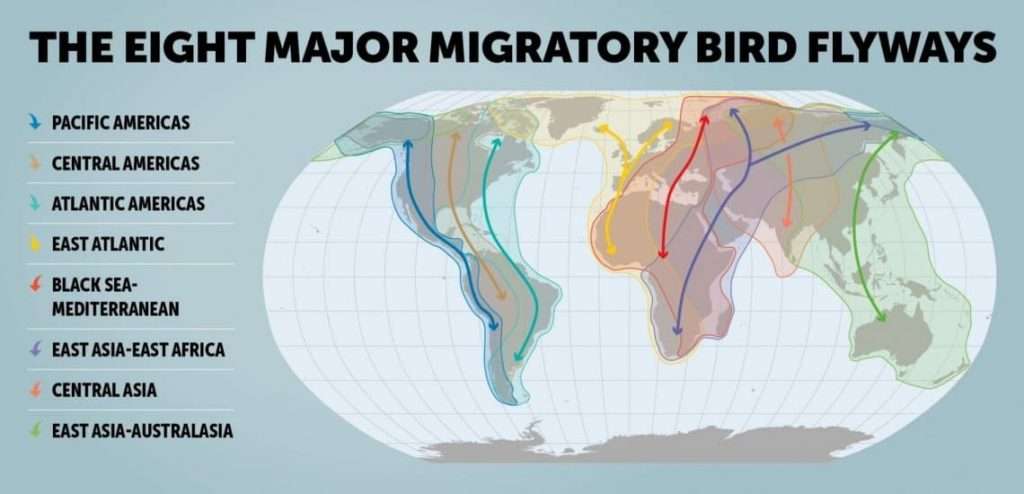

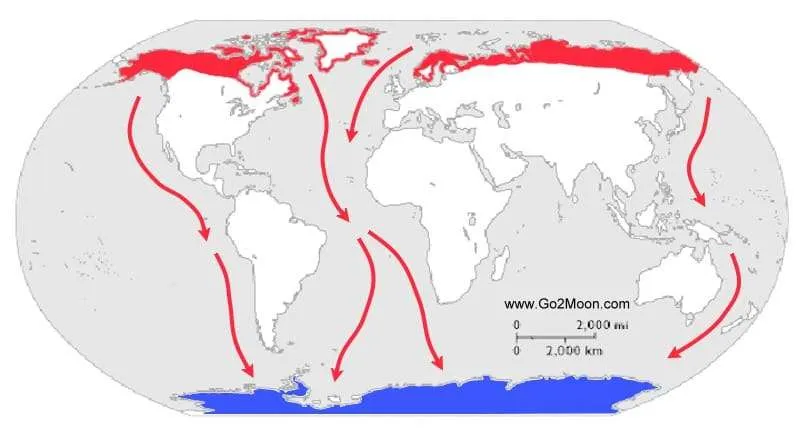

As food is one of the primary reasons for bird migration, their travel is linked directly to the availability of vegetation. Many bird species therefore leave areas of depleting vegetation and arrive in areas with increasing density of vegetation. Many birds migrate between the Northern and Southern hemispheres. Birds migrate along lines called ‘flyways’ which offer the best paths for birds.

The birds leaving Europe during its autumn usually fly east and west to try and avoid the ‘barrier’ of the Mediterranean Sea. Smaller birds, with enough energy to keep going will cross wherever they can, however larger birds will often make towards the narrowest crossing points.

Birds in North America fly towards Central and South America. The paths they choose are usually following coastlines or mountain ranges. Whether they are traveling a few miles or thousands, birds are migrating to avoid conditions that are a threat to their survival. Winter in North America means that the flowers that the ruby-throated hummingbird drinks nectar from disappear, leaving no choice for them other than to travel to Central America for the winter where food is plentiful.

The map below shows the eight major migratory routes that the migratory bird species follow.

These migration routes have developed over thousands of years of adaptation. Due to competition for food and nesting space, it is likely that some species have ventured further from their usual habitats. Climate change and human impact have also taken their toll on bird migration.

National Geographic writes that conservationists estimate that every year between 11 million and 36 million birds are captured or killed in the Mediterranean region alone, threatening birds like the chaffinch and the blackcap. Habitats in sub-Saharan Africa have also become less welcoming as increasing agriculture means that more land is cleared of the vegetation vital to some bird’s survival.

Which bird migrates the furthest? How far do they go?

The Arctic Tern, tiny as it might be, is known as the world’s longest migrator. Every year, this little bird flies from the Arctic Circle to the Antarctic Circle, an arduous round trip of about 30,000 kilometres (18,641 miles). However, because they follow a strange zig-zagging pattern that means they don’t have to fly into severe winds, the journey is probably longer every year. Arctic terns are perfectly built for migration. They prefer gliding in the air, letting ocean breezes carry their lightweight frames for great distances, they can even sleep and eat whilst gliding!

The Bar-tailed Godwit is another bird with a lengthy migration, travelling from Alaska to New Zealand. Astoundingly, they do not stop along the way, flying more than a quarter of the way around the world (a distance of around 11,000km or 6,835 miles) for 8 or 9 days straight. It’s the longest non-stop migration ever recorded. To complete this incredible feat, the godwits, like many of their long-haul cohorts, have to prepare before undertaking the journey. They spend weeks building up huge fat reserves (essentially their fuel) so that by the time they leave, more than half of their bodyweight is fat.

How many bird species migrate?

Nearly half of known bird species, around 4000 species, are classified as regular migrants, meaning they make their international journeys every year moving from one habitat to another with the changing seasons. As we learn more about the habits of birds in tropical regions, this number is likely to increase. Not all bird species need to fly to migrate. Many populations of penguins migrate by swimming and Emus, the large Australian bird, will often travel for miles on foot to find food.

Of these 4,000 or more species of migrant birds, most breed in the northern latitudes of the hemisphere. To fulfil their migration goals, these species will all follow different patterns be it in route, speed and timings. Some complete their migratory routes in a very short time, particularly certain aquatic species, and others will make a more leisurely trip, often stopping along the way to feed.

Some species of warbler are known to take up to 60 days to travel from their winter habitat in Central America to their summer breeding areas in Canada. Many of the smaller species migrate at night and feed by day and others migrate primarily in the daytime.

How do migrating birds know where to go?

Many birds are known to follow landmarks, such as rivers and coastlines, although there are many who are comfortable flying directly over large bodies of water on their routes. In 1951, German ornithologist Gustav Kramer performed experiments that showed that European starlings relied on the sun as a compass during their migration journeys. For those species that migrate at night, ornithologist Stephen Emlen conducted planetarium research that showed that the same can be said for the impact of the ‘star compass’ as a navigation tool.

Extensive research has also shown that birds possess an internal magnetic compass which they use to orientate themselves along with cues from the sun and stars. There are also some species of bird have a mineral called magnetite in their beaks, which may help their navigational skills as it is sensitive to Earth’s magnetic field.

There are many species, particularly waterfowl and cranes, that follow the same migratory route year after year, even using the same stop-off points because of their plentiful food supply. Some young birds also learn the routes from their parents. If the birds are raised in captivity then humans have been known to teach them, this video shows whooping cranes being taught to migrate by a light aircraft!

Dalat Plateau Birding Herping and Wildlife Tours

The Dalat Plateau, rising 2,000 meters above sea level, is one of Vietnam’s most important [...]

Cat Tien National Park Birding Herping and Wildlife Tours

Cat Tien National Park tours offer an unforgettable experience with sightings of Germain’s Peacock Pheasant, [...]

Western Black Crested Gibbon – Nomascus concolor

Nestled within the verdant landscapes of Vietnam, the Western Black Crested Gibbon (Nomascus concolor) emerges [...]

Northern White-cheeked Gibbon – Nomascus leucogenys

The northern white-cheeked gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) is a Critically Endangered gibbon species indigenous to South [...]

Northern Yellow-cheeked Crested Gibbon – Nomascus annamensis

The Northern Yellow-Cheeked Crested Gibbon, or Nomascus annamensis, is an exclusive primate species found in [...]

Eastern Black Crested Gibbon – “Cao-vit Gibbon” – Nomascus nasutus

Nestled within the dense, emerald-green forests of Vietnam, the Eastern Black Crested Gibbon (Nomascus nasutus), [...]