PART I: The largest biosphere reserve in Southeast Asia: Vietnam’s success story or a conservation failure?

Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve by Shreya Dasgupta on 30 September 2014 on mongabay.com

In 2010, poachers shot and killed the last Javan rhino in Vietnam, wiping out an entire subspecies. The Sumatran rhino, the Malayan tapir, and the civet otter, too, have disappeared from the country. Moreover, charismatic species like tigers, elephants, gibbons, and the secretive Saola discovered recently in Vietnam’s forests are at risk of extinction in the coming decades as threats to wildlife continue unabated in the country.

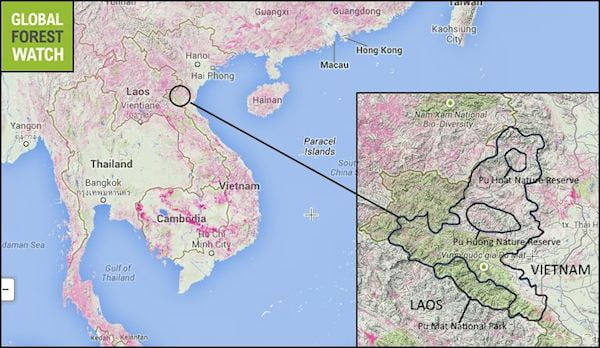

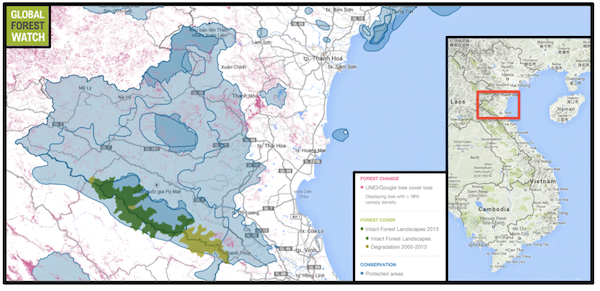

The thirteenth-most populous country in the world, Vietnam also has one of the highest GDP-growth rates among Southeast Asian countries. In addition, it is a major hub for the consumption and supply of wildlife-related products. It is thus no wonder that Vietnam has been fast depleting its forest resources. According to Global Forest Watch data, the country lost almost 1.2 million hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2012.

Northern white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys), in Vietnam. In this species, the females are golden and the males are black. They are listed by the IUCN as Critically Endangered. Photo by Terry Whittaker.

To protect Vietnam’s rich biodiversity, the government has established over 100 protected areas till date. In addition, Vietnam joined UNESCO’s World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR) in 2000. The WNBR consists of a network of sites called Biosphere Reserves, aimed at integrating people and nature for sustainable development. So far, UNESCO has designated eight such voluntary Biosphere Reserves in Vietnam. The Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve, designated in 2007, is the largest of these reserves.

Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve

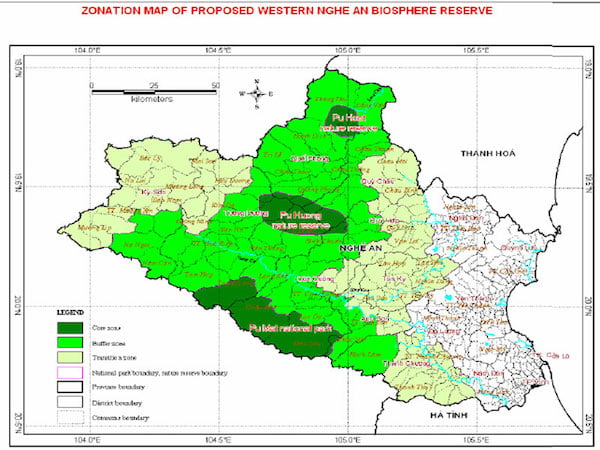

With an area of 1.3 million hectares, Western Nghe shares 440 kilometers (about 273 miles) of its boundary with neighboring Laos. The biosphere reserve contains three important protected areas – Pu Mat National Park, Pu Huong Nature Reserve, and Pu Hoat Nature Reserve – home to several threatened, rare, and endemic species. Western Nghe An also has many ethnic groups residing within, such as the Thai, Mong, Tay Poong, and Kho Mu.

While Western Nghe An was recognized as a biosphere reserve in 2007, it was only in 2011 that the Nghe An People’s Community officially accepted UNESCO’s recognition.

Talking to “Voice of Vietnam” (the country’s national radio broadcaster) in December 2011, Nguyen Thanh Nhan, the Director of the Pu Mat National Park said, “Why did we wait until now to declare the UNESCO recognition? First, we wanted to make the entire community aware of the fact that it requires a long process to gain this recognition. Second, the time is now ripe for the declaration. Since its recognition in 2007, any activities relating to the Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve have received serious interest from the provincial People’s Committee and relevant agencies. We understand that the recognition brings an honor and a brand name, but what we must focus on now is how to sustain this brand.”

A “brand name” would also increase investment in biodiversity research and improve biodiversity conservation in the region, Nhan added in the radio interview. But has it?

Between 2011 and 2013, the Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve suffered a net loss of about 4,000 hectares of tree cover, according to data from Global Forest Watch. In addition, media continues to report increasing depletion of forests and an increase in the consequent human-wildlife conflict.

Impact on gibbons

Depletion of forests is a major threat to Vietnam’s primates. The country has six species of gibbons that occur in small, isolated populations and are under constant threat of being driven to extinction. Each of these six species is currently listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered by the IUCN. In fact, Vietnam has some of the world’s rarest gibbon species, such as the eastern black crested gibbon with just about 100 individuals remaining in the wild.

The northern white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys), too, is a critically endangered species of gibbon, endemic to Vietnam, Laos and China. Almost extinct in China, fewer than 190 small groups of the gibbons currently occur in Vietnam, according to a 2010-2011 population estimation survey by Conservation International (CI) and Fauna & Flora International (FFI).

A major stronghold for these gibbons in Vietnam is the Pu Mat National Park. There, surveys found that of the 190 northern white-cheeked gibbon groups, 130 groups (with approximately 455 individuals) were found in Pu Mat. Surveys in Pu Huong and Pu Hoat Nature Reserves revealed dismally low numbers – only around 7 and 12 groups respectively.

Most of these gibbons are currently restricted to higher elevations along the Laos border. Unlike the lower elevations that face greater hunting pressures and loss of habitat, higher altitudes confer the gibbons some natural protection, according to a report by CI and FFI.

So has the declaration of the Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve improved protection for these threatened primates? Not yet, some conservationists think.

“The declaration of the Biosphere Reserve alone does not mean that protection in the area has been improved significantly, and that forest exploitation like hunting or logging is completely eliminated,” said Ulrike Streicher, a wildlife veterinarian who has worked with primates in Vietnam. “Only if these activities are controlled, the gibbons will benefit from the Biosphere Reserve.”

Nguyen Manh Ha, a conservationist at the Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies at Vietnam National University, agreed. “The biosphere actually contributes nothing, or very little. The biosphere is just a ‘title,’ and is not recognized as an official protected area system in Vietnam,” he said. “And a ‘title’ without investing appropriate resources is not going to be effective.”

While Pu Mat is one of the largest remaining blocks of forests in Vietnam with the biggest population of northern white-cheeked crested gibbon, the gibbons within Pu Huong and Pu Hoat Nature Reserves remain isolated and are not connected to the Pu Mat populations. In addition, despite the legal protection of these forests, gibbon species in this region are under severe threat, according to Streicher. With no strong law enforcement, illegal deforestation continues despite the declaration of the area as a Biodiversity Reserve.

“The Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve borders large forest tracts in Laos, and if it is protected well, if the forests within it are connected by corridors and if transboundary conservation can be achieved, it will play an critical role as a refuge for wildlife populations in this region,” she said.

Streicher added that for the Biosphere Reserve to be effective, sufficient funds must be made available to ensure the establishment, boundaries and various regulations of the reserve and deploy appropriate staff to enforce them.

“It is also very important that the local population is aware of the reserve, and information and regulations concerning the reserve should be dispersed using all local media,” she told mongabay.com.

“Only when the local populations understands the purpose of the reserve and the regulations are strongly enforced the biosphere reserve will over time achieve its goals.”

PART II: Will ‘Asia’s unicorn’ survive? Hunting and deforestation continue in the Vietnam biosphere reserve

by Shreya Dasgupta on 2 October 2014 on mongabay.com

Encompassing 1.3 million hectares, Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve the largest such reserve in all of Southeast Asia. It straddles the border between northern Vietnam and Laos, and is home to many unique and threatened species. Because of the biological importance of the region, it was designated a biosphere reserve by UNESCO in 2007. But deforestation and bushmeat hunting continue, begging the question: is the wildlife of Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve truly protected?

Within Western Nghe An Reserve lives a large mammal at very high risk of extinction – the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), also called “Asia’s unicorn,” which was unknown to science until its discovery in 1992. Endemic to the Annamite Mountains of Laos and Vietnam, the saola still remains one of the rarest and least sighted large mammals in the wild. Its population status remains unknown, and despite being so rare, it has received little conservation attention and funding.

A female saola that was brought into a Laos village in 1996 nicknamed Martha. She died after only 18 days in captivity. Photo by William Robichaud.

According to data from Global Forest Watch, Vietnam lost more than one million hectares of forest from 2001 to 2013, representing about 7 percent of the country’s total forest cover. During the same time span, Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve lost about 3 percent of its forest cover. While this is an improvement over Vietnam as a whole, the rate of forest loss in the area did not change significantly after its induction as a biosphere reserve, with more than 25,000 hectares lost between 2007 and 2013.

Hunting is also a big problem in the reserve. It is this that poses the greatest threat to the saola.

“By the time deforestation or fragmentation is likely to be a threat (we think), the saola will already be long gone,” said Nicholas Wilkinson, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge, who works on the conservation of Saola in Vietnam. “It would be like… I don’t know… worrying about the effects of climate change in Syria – potentially very serious in future but just not the current area of concern.”

William Robichaud, Coordinator of the Saola Working Group, agreed that controlling hunting was the way to go for now. “Snares need to be removed and gun hunting needs to be reduced in key saola sites to save the species from going extinct in the near-term, while working on long-term attitudinal changes,” he said.

According to Cao Tien Trung who works for the work for Center for Environment and Rural Development at the Vinh University and is a member of the Saola Working Group, current management regulations are not very effective for the conservation of wildlife. Trung advocates for community-based conservation.

“The relationship between local communities surrounding the NR and forest resources should be recognized as it has existed for a long time – men have long been involved in hunting and women in collecting other forest products,” he said.

Trung added that conservation in Vietnam is largely dependent on international funding and partnerships with international NGOs. And this is a matter of concern.

“While this brings in powerful ideas as well as money, it leads to an unstable situation and is one of the causes of widespread conservation failure in the country,” he said. “Domestic environmental NGOs are restricted in their field of operation and have a largely urban base. Community-based organizations, we believe, are crucial to the future of conservation in Vietnam but require long-term support and stable relationships with their supporters, something which international projects cannot easily provide.”

Verdict?

The biosphere reserve model of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Reserve Program does emphasize conservation efforts that are people-centric. However, in many cases and particularly in developing countries like Vietnam, this conservation model often remains only on paper. While representing international recognition, a biosphere reserve falls under the jurisdiction of individual member countries. These regions often do not have the legislation, logistics or resources to ensure that goals of the biosphere reserve model are met.

In a paper published last year in Biological Reviews, researchers reviewing the effectiveness of biosphere reserves across the world wrote, “For the Biosphere Reserve model to be successful long term, it requires political buy-in at the level of state/provincial or national government, and if popular political benefit is seen to be absent, it is unlikely that these governments will continue to support the ideals of the Biosphere Reserve concept.”

Close-up of WWF camera trap photo of saola taken in September 2013. Photo by WWF.

Crocodile Trail – The Best Birding Trail in Cat Tien National Park

If you’re a birder or nature photographer planning a trip to Vietnam, few places offer [...]

Cong Troi Trail – Top 1 Dalat Plateau Birding Trail Experience

If you’re a birder or nature photographer planning a trip to Vietnam’s Central Highlands, the [...]

How to Identify the Greater Sand Plover, Tibetan Sand Plover and Siberian Sand Plover

ContentsPART I: The largest biosphere reserve in Southeast Asia: Vietnam’s success story or a conservation [...]

Highlights of Cat Tien National Park Reptiles and Amphibian Endemics

Spanning over 71,350 hectares of tropical forests, grasslands, and wetlands, Cat Tien National Park is [...]

Highlights of Cat Tien National Park Mammals in a World Biosphere Reserve

In addition to reptiles and birds, Cat Tien National Park is also rich in mammals, [...]

Kontum Plateau Endemic and Highlight bird

Kontum Plateau Endemic And Highlight Bird species like Chestnut-eared Laughingthrush and top birding routes while [...]