This post takes note of Viet Nam Ecotourism from the document “Ecotourism in Costa Rica and Vietnam: Is It Sustainable?” FULL report 2016 here (Research Gate)

At a fancy restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), a customer can order bear, deer, porcupine, cobra, or bat. Pangolin, or the scaly anteater, is now the most illegally trafficked animal in the world; it can be had for $150 a pound at the same restaurant. The ability to consume wildlife is a mark of high status in Vietnam, as well as in surrounding Asian countries.

The demand for rare species as pets, as well as for consumption, has resulted in Vietnam becoming a hub for the market of illegal wildlife and products coming from Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Africa, both for local consumption and transshipment to China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Hong Kong.

Though Southeast Asian countries have passed laws against the illegal trafficking of wildlife, they are markedly ineffective in Vietnam. Police in a northern province of Vietnam seized 42 live, endangered pangolins from poachers, fined the perpetrators, and gave them to the forest rangers for safekeeping. The rangers in turn sold the pangolins to local restaurants. The small fines that result when people are caught are not sufficient to stem the trade.12

There are two related reasons why many species are imperiled in Vietnam. The first relates to a culture in which the consumption of wildlife is normal and if one can afford it, a sign of high status. The second reason is poverty. While Vietnam has made significant progress over the last decades in reducing poverty, it remains especially high in rural areas, mountainous regions, and the central highlands.

The average per capita income in Vietnam is $1890, and even lower in rural areas. The average income of a farming family is $70 per person. That provides a strong economic incentive to benefit from the illegal sale of wildlife. A star tortoise smuggled out of Vietnam is worth around $4500 and a soft-shelled turtle sells for $1,000. The need to reduce poverty has meant that the government has provided little pressure on the tourism industry to develop sustainable practices.

As the travel agency, Frommer, notes: “There is virtually no backlash for hotels and resorts’ profligate energy use. Meanwhile, the enthusiasm of international hotel chains and local developers has led to massive development of once-public, pristine beaches.” Tourism has, so far, contributed to environmental degradation and the deterioration of biodiversity.

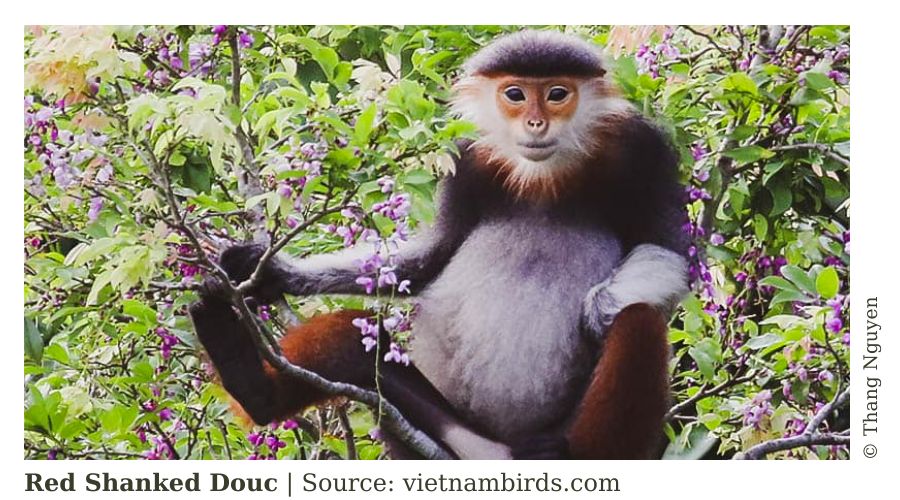

Like Costa Rica, Vietnam is home to some of the richest and most diverse ecosystems in the world. There are at least 310 species of mammals, 2000 species of marine fish, and 162 species of amphibians. There are 1000 species endemic to Vietnam and more are being discovered. In fact, of the last 10 mammals discovered in the past two decades, 8 were found in the jungles of Vietnam.

But the forests that protect these unique species are fast disappearing. The devastation began when the U.S. sprayed thousands of acres of forest with the defoliating Agent Orange. Following the war, and the opening up of the country’s economy in the 1980s, both legal and illegal logging proceeded apace reducing forest cover by 50%.

The government of Vietnam has established 16 parks and 14 reserves to protect the natural world and, specifically, to 13 attract tourists to help drive economic development and raise people’s standard of living. While making progress on the economic front, they are losing on the environmental front, even though the government has a stated commitment to sustainability. The eight million visitors who arrived in 2015 may not, however, be Vietnam’s biggest problem in meeting sustainability goals.

Climate change.

The World Bank has indicated that Vietnam is one of the top five countries in the world most likely to bear the costs of climate change. It is expected that both low and high temperatures will be more extreme and the amount and timing of rainfall less predictable. The two major deltas that supply Vietnam with much of its food are already being impacted.

During the dry season, brackish seawater already penetrates as far as 37 miles up the Mekong Delta, killing crops and forcing farmers to either leave or find new ways to make a living. Rising sea levels, driven by global warming, will only exacerbate this situation. A one-meter rise (3.3 feet) in sea level would flood a quarter of the delta and leave 5 million homeless.

Currently, about 30% of all Vietnamese live in the Mekong Delta and make their living from agriculture and fishing. The Delta has been referred to as the “rice stomach” of the nation and it is the source of most of Vietnam’s fish products. The government’s response to this emerging crisis is to work with farmers and fishermen to adapt by shifting from growing rice to raising fish and shrimp in ponds.

In the Red River Delta, they are building a series of dikes to prevent the incursion of salt water. But there are other problems than those created by climate change that will affect how people make a living and whether or not tourists will visit.

Dam building

The Mekong River, at 2500 miles, is the world’s 12th longest. It starts as a small stream in Tibet, passes through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia, ending in Vietnam. The river deposits 35 billion cubic feet of soil each year in the Delta, replenishing the soil and depositing nutrients that sustainable agriculture and fisheries.

Growing demand for hydropower 14 among Vietnam’s neighbors is likely to bring this to an end. China already has five dams on the river and plans to build 14 more. Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia have 10 planned or under construction. All of them will limit the movement of fish and drastically reduce the yearly deposits of soil on which the Delta farmers and fishermen depend.

The combination of climate change and dam building will also have an effect on the tourist industry. Cultural tourism will disappear because farmers in conical hats will no longer be planting or harvesting rice. Those casting nets in the delta from their small boats will be fewer.

The floating market of Cai Rang

Where people haggle over the price of fruit, clothing, and other market items is a growing destination for tourists, but it is threatened by climate change and dam building. The floating market of Cai Rang. Can Tho City be Vietnam’s fourth largest with a population of over 1.5 million?

Located about 100 miles south of Ho Chi Minh City, it sits on one of the largest tributaries of the Mekong and is known for its floating markets, canals, and Buddhist pagodas. Tourists who come to Can Tho City can take a 6-hour round-trip by boat to explore the floating market of Cai Rang. The market originated as a way for buyers and sellers in the Delta to come together in a convenient location—the middle of the river.

Travel from farm to farm along the river occurs almost exclusively by boat and those who fish trade their catch for fruits and vegetables or transport them to the harbor at Can Tho. Early in the morning hundreds of small boats appear selling a variety of goods: bitter melons, mangoes, squash, pineapple, tomatoes, bottled drinks, coffee, fish, flowers, and even dresses. Some boats are floating food stalls selling things like pork noodle soup. The boats ferrying tourists, some chewing on pieces of pineapple skewered on a stick, weave in and out of the crowded marketplace.

This form of cultural tourism has little impact on either the economy or the ecosystem of the market. But 15 changes will come to the floating market and, if it still exists a decade from now, few tourists will realize how it has changed. The impact of tourism on a new destination is, however, quite visible.

Phu Quoc Island.

The island lies 25 miles south of the tip of mainland Vietnam and serves as an example of the buccaneering form of tourism that has evolved, where private developers and local and provincial governments open up pristine areas to draw in eco-tourists to boost the economy.

The government has indicated they plan to “develop the island into a high-quality eco-tourism destination by 2020,” while setting aside 50% of the island as a national park. Unlike Costa Rica, Vietnam allows hotels to be built directly on the beaches.

There are 180 different choices in accommodations on the island, ranging from massive luxury hotel complexes to cheap bungalows and hotels for backpackers. Though billed as a destination for eco-tourists, the only venue offered is a tour of a bee farm. Other options include visiting the famous prison built by the French to imprison and torture liberation fighters, as well as theme parks with water slides, a merry-go-round, and a Disney-like castle.

Temple and Pagoda tours are available along with motorcycle tours of the island. Although the jungle contains numerous species of mammals, plant life, and birds, there is a Safari Park with ostriches, rhinos, monkeys, and giraffes for the less intrepid to see. For those who don’t want to go snorkeling, there is an aquarium.

The island is made up of contrasts. The major hotels have groomed clean beaches while close masses of garbage have come in with the high tide. The rubbish and waste from hotels, fishing boats, and fish farms, total over 180 tons each day. There is no place for the hotels to dispose of their waste, so it ends up in a dump in the jungle. Untreated wastewater from hotels 16 and resorts is dumped directly into the ocean.

Recognizing the negative impact all of this has on the environment, the government has planned a number of projects, including the building of a waste-treatment facility, by 2020. In the town itself, grey water is poured directly into the street, and solid waste filters into primitive septic systems. There is only one hotel Mango Bay, which advertises itself as sustainable.

They minimized their impact on the environment by situating their buildings and using local materials for building. They buy local fish, poultry, and fruit to serve to their guests, minimize the use of water and electricity, and are one of the few hotels that have a septic system. Tourists, though, need to take the lead in choosing sustainable venues.

How to Identify the Greater Sand Plover, Tibetan Sand Plover and Siberian Sand Plover

Identification Differences within the Sand Plover Complex: The sand plover group, which was traditionally divided [...]

Highlights of Cat Tien National Park Reptiles and Amphibian Endemics

Spanning over 71,350 hectares of tropical forests, grasslands, and wetlands, Cat Tien National Park is [...]

Highlights of Cat Tien National Park Mammals in a World Biosphere Reserve

In addition to reptiles and birds, Cat Tien National Park is also rich in mammals, [...]

Kontum Plateau Endemic and Highlight bird

Kontum Plateau Endemic And Highlight Bird species like Chestnut-eared Laughingthrush and top birding routes while [...]

Dalat Plateau Endemic and highlight bird

The Dalat Plateau is a birdwatcher’s paradise, renowned for its exceptional biodiversity and unique highland [...]

Cat Tien National Park Endemic and Highlighted Birds

Covering 71,920 hectares in southern Vietnam, Cat Tien National Park is home to a number [...]